What Malaysia’s new Social Stock Exchange means for your Ringgit

December 16, 2025SEA Has Some of the Highest Breast Cancer Screening Rates in the World — and Some of the Worst Mortality Outcomes

Intro

One in eight women in Southeast Asia will be affected by breast cancer in her lifetime. Across the region, this translates to nearly 500,000 women living with the disease at any given time. Countries including Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand collectively lose around 130 women every day to breast cancer.

On the surface, the region appears to be making progress. Screening programmes exist. Awareness campaigns are widespread. Mammography services are available in both public and private settings. Basic knowledge of breast cancer doesn’t seem to be an issue.

Survival outcomes, however, tell a different story.

Regions with comparable — and in some cases lower — detection rates achieve markedly better mortality outcomes than Southeast Asia. This gap is consistent, measurable, and persistent across countries with very different income levels and health system structures.

So what happens after detection? What does that journey look like once women enter the healthcare system? And why, in a region where screening is expanding, do mortality rates remain so high?

For context, female breast cancer remains among the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide.

Writer’s Note

ASIR (Age-Standardised Incidence Rate): Measures how often cancer occurs after adjusting for age differences across populations.

ASMR (Age-Standardised Mortality Rate): Measures the risk of death after adjusting for age differences.

Taken together, these indicators allow meaningful comparison between countries with different population structures.

A Global Contrast

Only seven countries are currently on track to meet the World Health Organization’s target of a 2.5% annual decline in cancer mortality: Malta, Denmark, Belgium, Switzerland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Slovenia. All are high-resource economies with mature, well-integrated health systems.

Much of the developed world follows behind at varying distances. Southeast Asia lags.

When viewed through incidence rates alone, the region appears to be progressing. Screening is happening. Detection rates are rising. Awareness campaigns are clearly reaching people.

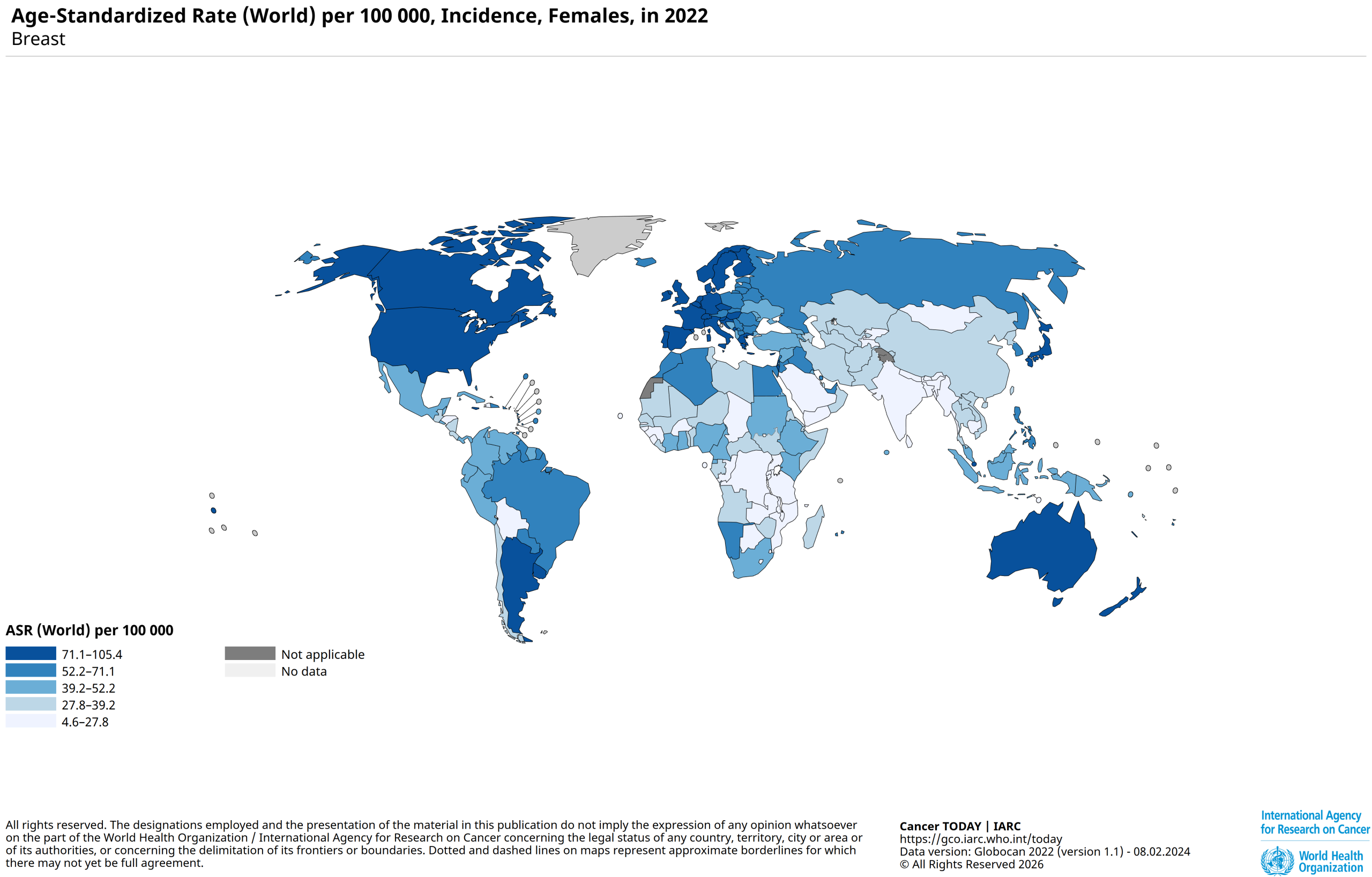

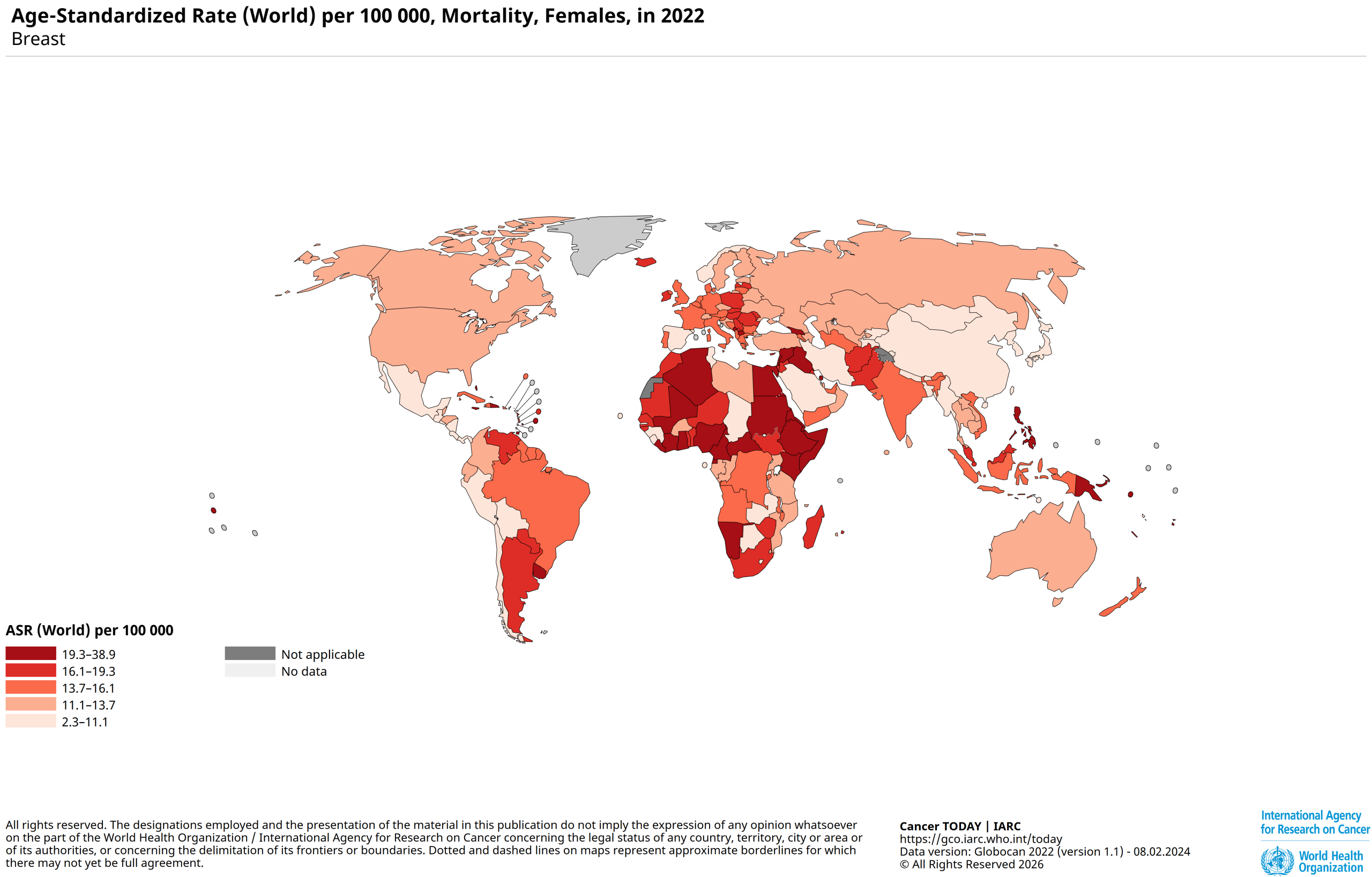

Mortality rates, however, tell a different story. In several Southeast Asian countries, breast cancer death rates approach those seen in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, where ASMR exceeds 20 per 100,000. This pattern persists even as healthcare spending and infrastructure expand.

At first glance, this may seem predictable. Wealthier countries tend to perform better. Lower-income countries struggle.

That explanation, however, does not hold up under closer scrutiny. Southeast Asia is not uniformly poor. Many countries in the region have expanding healthcare infrastructure, growing specialist capacity, and rising health expenditure. Yet mortality remains stubbornly high.

Hence, the discrepancy points out a strong bottleneck in the region’s healthcare system.

The stark difference between Southeast Asia’s incidence rate and mortality rates implies that there are systemic failings or large gaps in the healthcare journey.

A Bottleneck Under Pressure

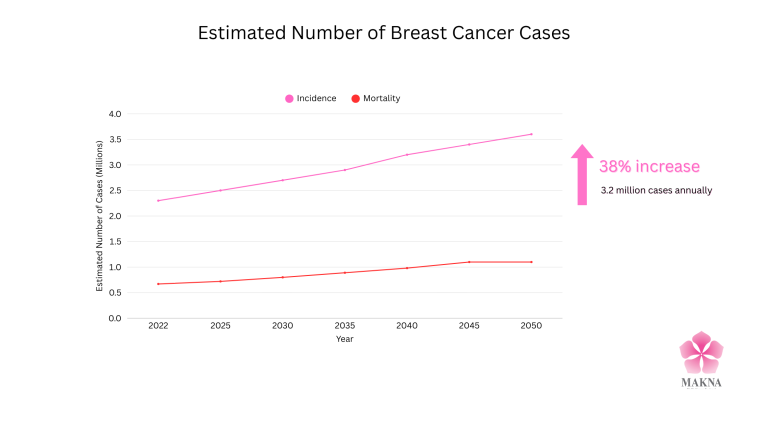

By 2050, the World Health Organization projects 3.2 million new breast cancer cases annually, a 38% increase from today. Deaths are expected to rise by 68%, with the largest burden falling on low- and middle-income countries.

In Asia alone, breast cancer mortality is projected to rise by 27.8%, while incidence increases by 20.9%. Among women under 50, the region is expected to surpass Western countries on both measures.

A high incidence rate can often be misread. It doesn’t automatically reflect poorer lifestyles, worse genetics, or uniquely risky behaviour.

Dietary habits, consumer culture, and everyday behaviour now cross borders with ease. Patterns that once differed sharply by geography have converged. Someone in Seoul is just as likely to eat as many cheeseburgers as someone in New York is to cook kimchi jjigae at home. Cultural differences persist, but they no longer explain stark disparities in cancer outcomes.

More often, a rising incidence rate reflects the reach of a healthcare system. It suggests that awareness efforts are working, screening services are accessible, and people are being encouraged to seek testing.

In that sense, incidence can actually be read as progress.

The problem occurs when diagnosis does not translate into survival. Across Southeast Asia, countries with the highest detection rates are often the same countries with the highest breast cancer death tolls. Women at risk are being found, but they are not being carried through to treatment with the same consistency.

Late Detection

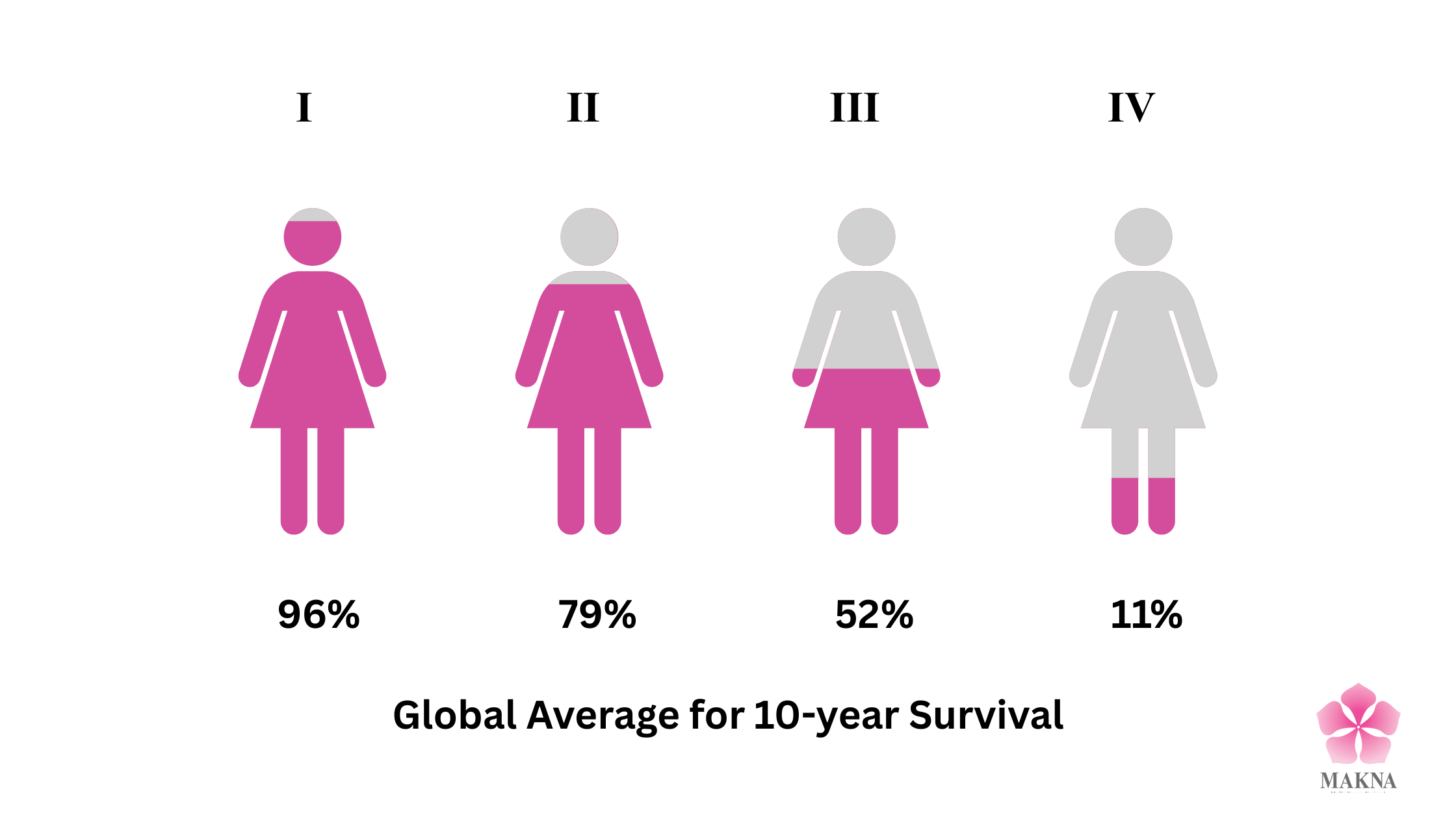

In Malaysia, around 50% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed at Stage 3 or Stage 4. At these stages, treatment is more aggressive, more costly, and far less likely to result in long-term survival.

Patients diagnosed at Stage 1 or Stage 2 have survival rates between 93 and 99 percent. At Stage 3, survival drops to roughly 80 percent. By Stage 4, it falls sharply to about 31 percent.

These figures mirror global trends.

Organized Vs. Opportunistic Screening

Between diagnosis and recovery lies a fragile, easily disrupted pathway.

In an organised breast cancer screening system, detection is not a one-off event. Women are proactively invited to screen, results are centrally recorded, and abnormal findings trigger defined referral and recall pathways. Follow-up is built into the system itself, reducing reliance on individual persistence or chance re-entry into care.

That infrastructure remains largely absent across much of Southeast Asia. Screening in the region is predominantly opportunistic. Women are screened when they encounter the health system — during an unrelated clinic visit, through employer initiatives, or when mobile and outreach services temporarily reach their community. These encounters improve access and raise detection, but they are rarely embedded within systems designed to ensure continuity once abnormalities are found.

As a result, women may receive abnormal screening results — findings that require further investigation rather than an immediate cancer diagnosis — and be advised to seek additional imaging, most often an ultrasound. What follows is uneven. Appointments may be delayed, referrals might move slowly, and diagnostic confirmation could stretch across weeks or months. Follow-up depends heavily on women returning on their own initiative, with limited system escalation when they do not.

This gap is visible to organisations working closest to communities. MAKNA, through its mobile mammogram programme, delivers a structured screening intervention that reaches women who might otherwise be missed. It is, however, only one small part of a much larger care ecosystem. Once abnormalities are detected, onward referral and treatment depend on hospital capacity, coordination, and pathways beyond any single organisation’s control.

Where screening functions this way, women enter the health system through different doors, at different points, with no assurance that those doors connect. Detection initiates contact with the system, but it does not guarantee progression through it.

Early detection stumbles in the handover. Somewhere between an abnormal result and a treatment plan, momentum is lost and the consequences spread unevenly. That loss is then absorbed by women deciding what can be delayed, what can be afforded, and what can wait and what can’t. Those decisions are rarely casual. They take shape under pressure — structural, social, and financial — in ways that complicate simple ideas about choice.

Why Women Do No Reach Treatment

Breast cancer discourse in Southeast Asia often centres on detection: screening rates, mobile units, awareness campaigns. The implicit belief is that once cancer is identified, care naturally follows.

For many women, this is not the case.

Across the region, a significant proportion of women who are screened or diagnosed do not move smoothly into treatment. Some experience prolonged delays. Others begin treatment late. Some never complete it at all. These outcomes are not random. They emerge from the gaps, flaws, and unfair realities in our healthcare pathways, social structures, and financial systems.

Macro Barrier: Structural Constraints in the Health System

At a system level, access to timely treatment is shaped by capacity, geography, and coordination.

Public hospitals across Malaysia and much of Southeast Asia operate under sustained strain. Oncology clinics are crowded. Specialist appointments are limited. Diagnostic services such as biopsies, pathology, and advanced imaging are unevenly distributed, with resources concentrated in major urban centres.

Referral pathways remain fragmented. Medical records do not always transfer seamlessly between facilities. Follow-up often relies on patients returning independently rather than on active system tracking. Missed appointments rarely trigger escalation.

For women living outside urban centres, these gaps widen further. Travel to tertiary hospitals can require several hours each way, repeated visits, and extended absences from work or family responsibilities. Each appointment carries direct and indirect costs.

Research consistently links longer diagnostic and treatment intervals with poorer survival outcomes, yet delays remain embedded within routine care. Waiting is normalised rather than treated as a systemic failure.

As a result, the burden of navigating care falls disproportionately on the patients.

Micro Barrier: Social Roles and Everyday Pressures

At an individual level, we have to admit that women have it harder than men.

Across Southeast Asia, women continue to shoulder the majority of unpaid care work. They manage households, care for children and elderly relatives, and often contribute to family income through informal or insecure employment. Getting sick disrupts this balance immediately.

Cancer treatment demands time, mobility, and sustained engagement with healthcare services. Hospital visits conflict with caregiving responsibilities. Treatment schedules interfere with work. Recovery reduces physical capacity.

For many women, prioritising treatment means redistributing responsibilities or leaving gaps that families may not be able or willing to absorb.

Support from partners and families is uneven. Some women are encouraged to seek care. Others are advised to delay or minimise symptoms. In more conservative communities, illness still carries stigma, making disclosure and early action socially costly.

Decision-making power is also uneven. Financial dependence, family hierarchies, and social expectations shape whether treatment is pursued and sustained. Healthcare becomes a shared decision, even when the consequences are deeply personal.

Financial Toxicity: When Treatment Becomes Unsustainable

And given all that, even when services are available and social support exists, cost remains one of the strongest determinants of whether treatment continues.

The ACTION Study, which followed cancer patients across Southeast Asia, found that more than 45% experienced catastrophic health expenditure within one year of diagnosis, defined as spending over 30% of household income on medical care. Many patients depleted savings. Some sold assets. Others took on high-interest debt. A substantial proportion experienced long-term financial hardship. Poverty begets poverty.

These outcomes occurred even in countries with public healthcare subsidies.

Direct medical costs are only part of the burden. Transport to treatment centres, accommodation near hospitals, lost income, childcare, non-subsidised medications, and extended recovery periods accumulate steadily. For rural patients, travel alone can consume a significant share of household income. For informal workers, time away from work often means no income at all.

Women are particularly exposed to these pressures. They are more likely to work in unstable employment, less likely to hold comprehensive insurance, and more likely to absorb financial shock on behalf of their families.

Doing Right By Women

The easy answer is to say this gap can be closed with political will and better coordination.

That it requires regional collaboration, shared standards, pooled expertise, and the right mix of task forces and financing models. That with enough integration, screening could flow neatly into diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up, as if care pathways exist independently of the lives that move through them.

These answers are not wrong. They are just incomplete. The problem runs deeper than administration. It sits in how our societies are built — and who they are built for.

Women are expected to absorb delay, cost, and disruption as a matter of course. To reorganise care around households. To defer treatment for stability. To treat their own survival as negotiable. Health systems mirror those expectations. They rely on women’s flexibility, unpaid labour, and willingness to endure. When systems strain, women are expected to stretch.

Women also remain under-represented in decision-making spaces where health priorities are set, budgets are allocated, and trade-offs are normalised. Across ASEAN, women hold only around 20% of parliamentary seats and make up roughly 24% of middle and senior management roles. The spaces where priorities are decided remain overwhelmingly male. As a result, policies are designed around abstract patients, while real women navigate caregiving, informal work, financial precarity, and unequal power at home. The system technically offers care, but practically withholds it.

We often resist calling cancer a gender issue. Yet breast cancer makes the contradiction visible. A disease that is highly treatable becomes lethal when it collides with social expectations that quietly limit women’s choices. Not because women choose poorly, but because the range of choices available to them has already been narrowed.

If we want breast cancer outcomes to change, we have to do more than improve systems on paper. We have to confront how routinely women are asked to carry the cost of those systems failing.

Doing right by women is not an abstract moral claim. It is a design question. Until our health systems and the societies around them are built with women’s lives at the centre, early detection will continue to outpace survival.

And the gap will remain.

Thanks for reading!

If you liked what you read or would like to learn more, check out some of our other posts or read our quarterly publication, Neoplasia. And if you’d like to support us and the work we do, consider donating. Every little bit helps!